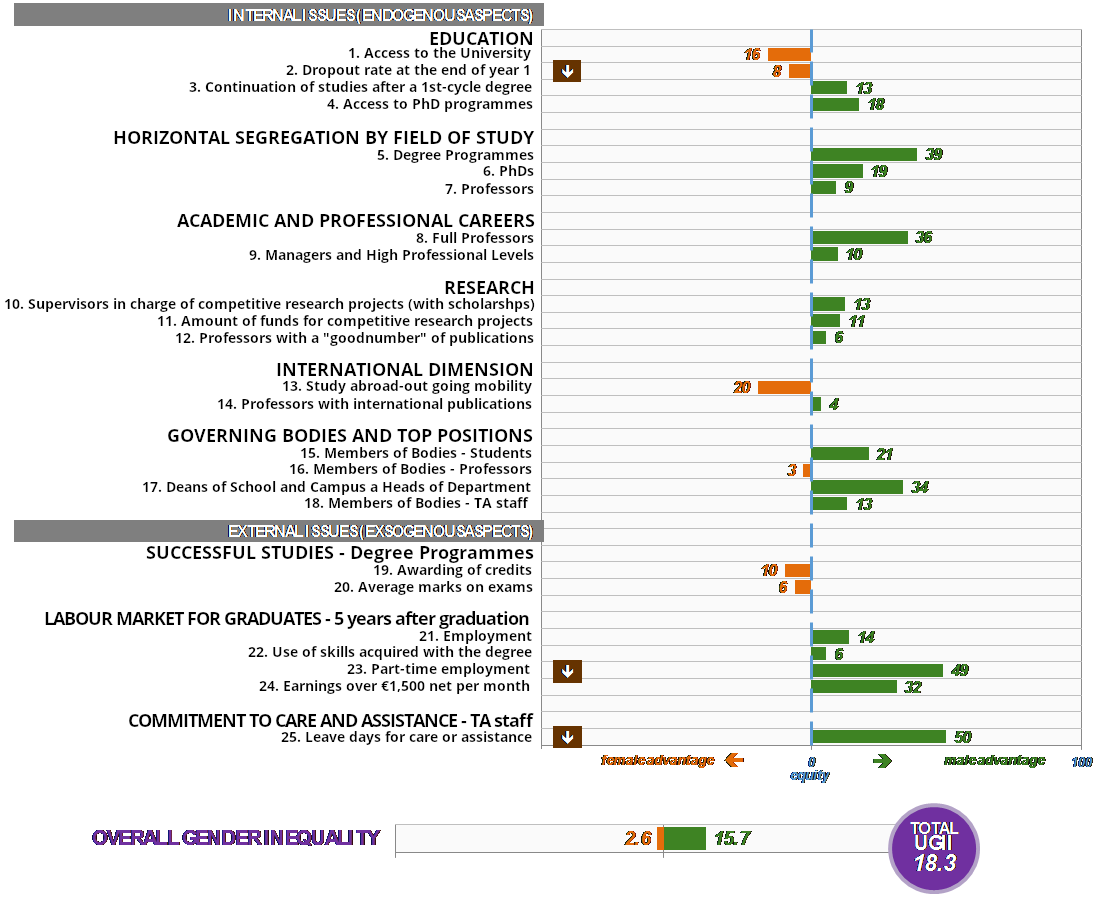

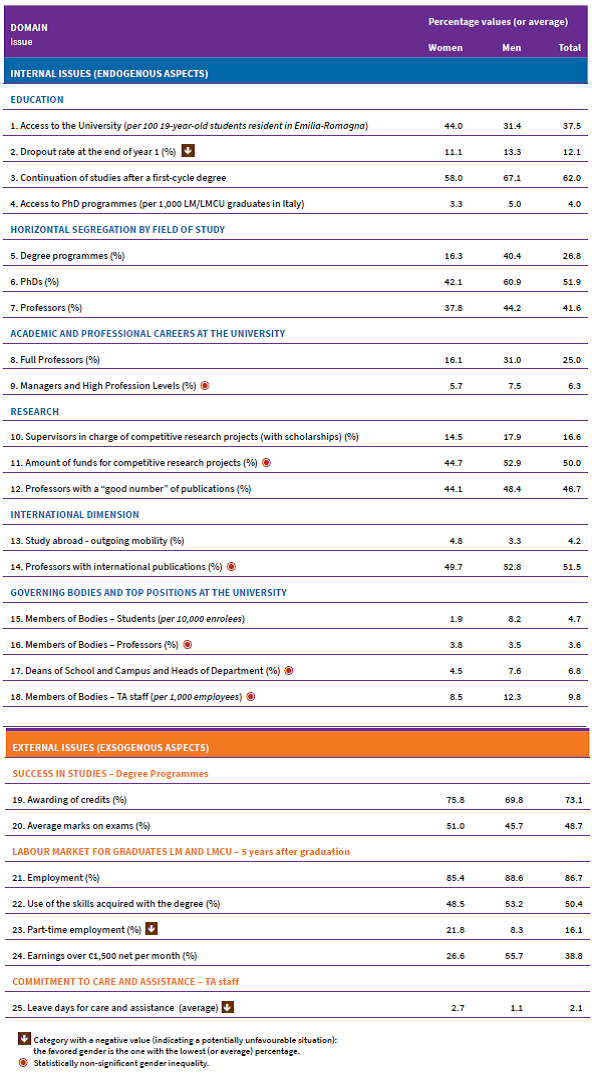

Figure 2 shows data for the 25 issues calculated at UNIBO in 2018, taken into consideration as the percentage of the maximum possible inequality. Notably, it emerges that women tend to invest more than men in the early stages of education: the number of matriculations as a percentage of nineteen-year-olds resident in the region is markedly higher for women than for men; female tend to abandon the degree programme less readily than men; they are more likely to regular acquisition of credits and their university exam scores, as well as take part more frequently to foreign study programmes. On the contrary, taking into consideration the second cycle degree, it emerges that male graduates move on more frequently than females from their first cycle to enrolment for a second-cycle degree programme and they are more likely to enrol for PhD programme.

Horizontal segregation – measured concerning the distinction between STEM/non-STEM students – clearly suggest the male advantage. Inequality by subject is also reported among PhD students and university professors, however to a less degree. Vertical segregation entitled in men’s favour is evident considering academic/professional careers at the university: in terms of full professors, 31% are among men and only 16% among women.

With reference to the TA staff, the presence of managers and employees in the high professional level category is higher for men, but the degree of inequality is rather limited (10% of the theoretical maximum). In the Research domain, gender differences are to the advantage of men, for the allocation of funded research projects, amount of funding, and publications by teachers.

Considering the Academic Bodies and Executive Positions at UNIBO domain we can note that in 2018, in the Bodies in which students are admitted (Student Council, Academic Senate and Board of Governors) overall, there are 30 men and only nine women; this leads to a 59% inequality. This is a worrying fact, reflecting a common attitude among young generations, who tend to disregard the problem of gender inequality on the presumed basis that it has already been resolved. Since the gender ratio in 2017 was much more balanced (23 men against 18 women), this aspect contributes significantly to the change in the UGII index between 2017 and 2018.

Among professors, the gap involves leadership position such as School Presidents, Campus Presidents, and Head of Departments, while members of university bodies show a more balanced situation; but it is necessary to keep in mind that the total population of potential faculty members of university bodies is already predominantly male. Finally, gender inequality in men’s favour emerges also for technical administrative staff.

Thus, it can be concluded that, concerning the possibility of reaching positions of responsibility within the university, gender equality is still quite far away.