Arantxa Gonzalez de Heredia, Ruth Esteban, Ainhoa Larrañaga

Mondragon University, Faculty of Engineering

Contact: agonzalezh@mondragon.edu

Arantxa Gonzalez de Heredia, Ruth Esteban, Ainhoa Larrañaga

Mondragon University, Faculty of Engineering

Contact: agonzalezh@mondragon.edu

Aim: To analyse the influence of gender on the design of hand tools as well as the influence of the design and communication of hand tools on the development of gender roles. To integrate sex and gender variables in the design methodology.

Methodology: Analysing the communication approach of the hand tool manufacturers, the perception of different user groups about the existing hand tools and the differences by sexes. Analysing the needs of users towards hand tools by sexes with the aim of determining if the existing products fulfil both sexes’ needs. Meeting the needs of both sexes can lead to better designs.

Gendered results:

The discussion of gender issues in design practice, or in design research is still in its infancy (Ehrnberger et al.). Gender equality and equity in design is often highlighted, but it often results in producing designs that highlight the differences between men and women, although both the needs and characteristics vary more between individuals than between genders (Hyde). According to these authors, the gender system or gender order is described as the power structure that organizes the relationship between sexes at the symbolic, structural, and individual levels. In addition, the gender system is built on the basic principles of separation and hierarchy.

The principle of separation is that behaviours and tasks are divided between men and women as opposites. A clear example of the principle of separation is how products are targetted at children. Division creates expectations for boys to be strong, intelligent and logical, and for girls to be beautiful, well behaved and caring (Kirkham; Rommes et al.). The same expectations pursue us throughout our life. Products aimed at women are characterised by soft, clean, organic shapes and light colours (preferably pink) and often with some kind of decoration such as hearts, diamonds or flowers. Products aimed at men, however, are characterised by complex and angular shapes and dark colours. Male-focused products resemble the aesthetics of machines and underline their effectiveness or express danger or challenge.

The principle of hierarchy considers masculinity as the true standard of human values and that what men do is superior to what women do. There are many examples where the language of a masculine product indicates superiority. These products are described with adjectives such as professional, exclusive or intelligent. More simple and economical versions of the same products tend to adopt a more feminine aspect (Schroeder; Shrum).

Women have been involved in design history in a variety of ways, but their influence on design has been systematically discouraged (Buckley). The aim of this study is to prove that these theories apply also to the market of hand tools.

Below the main objectives of the study are described:

1. The results of the first workshop demonstrated that the classifications made by each group clearly coincided (Graphic 1). Aesthetic codes are well known by both sexes, few doubts arose only with neutral designs where the female and male groups classified them as having been designed for their own sex. Despite different opinions about the suitability of the aesthetic codes, both teams coincided on the final classification. However, it is thought that this result might vary if the exercise had been carried out individually. It can be concluded that if a sex-neutral product is to be designed, certain colours should be used: white, grey, wood, orange; and certain forms: fluid, organic forms.

2. Eleven brands of drills were chosen from the Leroy Merlin DIY store’s website, in order to represent a variety of features. All the drills identified matched the male focused design codes. In order to prove that their communication is also aimed at males, commercial catalogues and websites were analysed. Sixteen commercial catalogues of hand power tools from those 11 different brands were analysed: Bosch, Black&Decker, Hitachi, AEG, Makita, Vito, Worx, Ryobi, Stanley, Dewalt and Fartools. The search for these catalogues was more complicated than expected, as companies use their online sales platforms to display options, thus saving on brochure printing. For this reason, catalogues from different years were selected (the oldest being from 2012) and images representing men, women and those where the sex was not clear, were numbered. It is important to point out that only photographs in which recognizable parts of the human body appear were taken into account. There are only photos of women in 2 of the 16 catalogues analysed, both from the brand number 8, from the years 2012 and 2018. In these two catalogues the percentage of female photos is still much lower than that of male photos, only 5 out of 18 and 2 out of 30 respectively.

The 11 brand websites were also analysed. In all of them, the visual impact of the frontpage only was evaluated, without clicking on any link or menu.

In this case, 4 of the 11 websites have photos of women: Brand 12, Brand 10, Brand 11 and Brand 8. In addition, Brand 10 and Brand 11, with a total of 2 snapshots each, have one of each sex, and use an impersonal language. This brand, uses videos of hands to exemplify the use of the drills.

There are no photos on the Brand 5 website, but it does state that they sponsor car Rallys, motorcycles, football and bull fighting. In this website the brand uses statements like “Sometimes bigger is better”.

From this analysis it can be concluded that brands reproduce gender stereotypes when presenting their products.

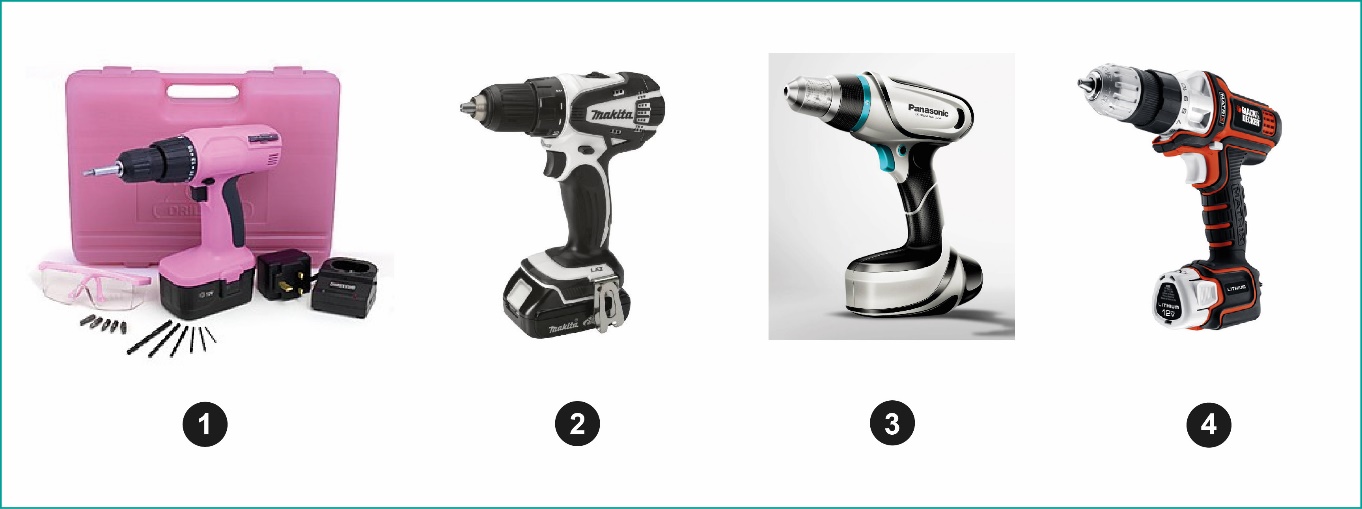

3. Regarding user needs, the results of the survey show that the percentages of use of a drill between sexes among the selected group of students is slightly different. 86% of the women and 97% of the men claimed to have used a drill at some time. However, when asked about the ownership of the drill 18% of the women and 59% of the men said that the drill was not their own. In addition, out of those who said that the drill did not belong to them, 30% said that it belonged to their father, 10,7% to their parents and only one said the drill belonged to their mother. Users were also asked to select one out of four models of drills shown below.

The selection was very similar for both sexes. Drill number 3 was the most popular, selected by 45% of the women and 47% of the men. Drill number 4 was selected by 29,4% of the women and 38% of the men. Drill number 2 was selected by 23,5% of the women and 26,5% of the men. And drill number 1, which is a clear example of “pinking”, was selected only by one woman (1,9%) that argued that she had never used a drill and that she would buy the most simple model. However, when asked about the features that users would expect from a drill, differences between sexes arose. For example, easiness to clean was mentioned by 9 women and no men and easiness of use was mentioned by 37 women and 18 men. Users were asked to put the 10 features in order of importance and two general rankings were created based on the number of times that the feature was mentioned and the importance given. Difference between sexes are bigger in the first ranking than in the second. See table 1.

From these results, it can be suggested that companies approach the female market by using stereotypical codes instead of taking into account the real needs of women. Despite the fact that women place more importance on the attractiveness of the tool, the pinking strategy does not work. The results demonstrate a small difference between men and women in terms of need when choosing a drill. However, this could be due to students being from the same degree in Industrial Design and Product Development Engineering. That is to say, they have studied the same design methodology that considers aesthetics, use and technical features. For this reason it was decided that repeating the same experiment with students from other degrees was necessary. A first trial for the repetition was therefore carried out on 26 students from the degree in Biomedical Engineering. The results showed that students had more difficulties naming 10 features and that there was a slightly bigger difference between sexes.

Buckley, C. “Made in Patriarchy: Toward a Feminist Analysis of Women and Design.” Design Issues, 1986, doi:10.1097/01.TA.0000020397.74034.65.

Ehrnberger, Karin, et al. “Visualising Gender Norms in Design: Meet the Mega Hurricane Mixer and the Drill Dolphia.” International Journal of Design, 2012.

Hyde, Janet Shibley. “The Gender Similarities Hypothesis.” American Psychologist, vol. 60, no. 6, Sept. 2005, pp. 581–92, doi:10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581.

Kirkham, Pat. “The Gendered Object.” Choice Reviews Online, vol. 34, no. 08, Manchester University Press, 2013, pp. 34-4773-34–4773, doi:10.5860/choice.34-4773.

Rommes, Els, et al. “Design and Use of Gender Specific and Gender Stereotypical Toys.” Gender, Technology and Development, vol. 3, no. 1, 2011, pp. 186–204, https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/103130/103130.pdf.

Schroeder, Klaus. Gender Dimensions of Product Design. 2010, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5dbe/834ffbfd897a4b6ce969bef139163714f024.pdf.

Shrum, Rebecca K. “Selling Mr. Coffee.” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 46, no. 4, Dec. 2012, pp. 271–98, doi:10.1086/669669.